The Kepner-Tregoe

Project Management Model

……History in the Making!

In the beginning…

…The beginning for

Kepner Tregoe was 1958…

It was then that Charles Kepner a social psychologist, and

Benjamin Tregoe a sociologist, were working for the RAND Corporation in California.

…and then that they “concluded that the process of gathering and organizing

information for decision making needed improvement” (Kepner & Tregoe, 1981).

The RAND Corporation was not interested. So Kepner & Tregoe “struck

out on their own” and started their own company.

Kepner Tregoe & Associates had a humble beginning. Their first office was in Tregoe’s garage (Kepner & Tregoe, 1965). Here was where they had some of their most important ideas. The research conducted there evolved into a 1965 book entitled “Rational Manager.” This book and the ideas it contained, became the basis for the Kepner-Tregoe training courses.

In the coming decades, Kepner and Tregoe became well known through the production of their training courses. It was in these courses that Kepner and Tregoe taught Decision Analysis and Potential Problem Analysis, mainly to senior and middle managers. The latter, Potential Problem Analysis eventually became a key component in their Project Management model.

The Kepner-Tregoe Project Management Model

Many of the best inventions, are not invented by just one person! Just as Alexander Graham Bell did not invent the telephone from scratch, Kepner & Tregoe (KT) did not invent much of their Project Management model. Bell brought together several devices developed by others to produce his invention - the telephone (Burke, 1978). So too, it was with the Kepner-Tregoe Project management model. This model was the synthesis of several methods developed throughout the twentieth century. A diagram of the Kepner –Tregoe Project management model is attached to this paper (Appendix A). In the next few sections, in addition to describing the KT model, I will attempt to describe the origins of many of the KT model components and end with a discussion of the model itself.

Definition Phase

The Definition phase includes the first four steps of the KT model. However as mentioned above these components were not invented by Kepner –Tregoe & Associates. This phase for instance is the combination of several management techniques developed in Education and Business in the 1930’s, 40s and 50s. It was during this period that business and education were concentrating on efficient practices for conducting work.

During the 1930’s Education was undergoing a struggle

between the conservatives and progressives. Perhaps the beginning of steps one

and two, in the KT model, is then with Ralph Tyler and his Eight Year study.

Ralph Tyler was appointed as the director of the evaluation staff for The Eight

Year Study (Tyler, 1975). This study compared different types of educational

practices. The practices are unimportant. What is important is that Tyler

conceptualized an objectives-based approach to educational evaluation (Worthen

and Sanders, 1987). In their report on The Eight Year Study, Smith and Tyler

provide an evaluation manual that becomes very influential in the years to come

(Smith and Tyler, 1942).

Seven years after this report with Smith, Tyler wrote his most famous work Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction. This simple book is important because it concisely describes his philosophy of educational objectives in simple logical terms. Tyler to this day has been called "the father of behavioral objectives." Even if a major implementation of his ideas was not realized until the 1960's with the works of his predecessors Bloom and Mager, we are still all indebted to Tyler's vision (Wilburg, 1998).

Mager’s work in the 1960s and 1970s further contributed to field of Educational Objectives. Dr. Mager was at this time a professor of experimental psychology at the State University of Iowa. He was also a well-known expert on the design, development and implementation of instruction. Like Kepner & Tregoe, Mager became well known for teaching workshops to business. As the president of Mager Associates, Inc., he assisted organizations for many years with solutions to instructional problems related to human performance (Mager, 1982).

Mager is perhaps best known for his process of Goal Analysis (Mager, 1982). Goal Analysis, in many ways, is the first two steps in the KT model. The Goal Analysis user, in this case the Project Manager, first states the Goal – The Project Statement. Then through a series of steps develops a set of Objectives.

The Project Statement

This first step in the KT model allows the user to define the project in a concise statement. As a part of this statement Kepner & Tregoe believe it is important to have an “Action word”, “an end result,” and “a target completion date (Kepner & Tregoe, 1993).” This is a Mager-like goal. Even though it is not one of Tyler’s behavioral objectives, it is similar in construction and gives rise to objectives as in Mager’s Goal Analysis. An important point set forth by Mager, Kepner, and Tregoe is that it is not necessary to define a goal in measurable terms. This Project Statement or Goal of the project is to state purpose and narrow scope. In addition to the above required elements of the project statement Kepner & Tregoe also believe it is important to include the cost; an important optional component of the project statement, that is if a budget is available.

Develop Objectives

As mentioned above objectives have become an important part of education. But “Management by objectives” is also a common approach to management in business. Kepner & Tregoe include this type of management in the second step of their model. In this way they allow a project manager to focus a project.

Peter Drucker first pioneered this approach to business management in the 1940s and 50s. Drucker who has since been called “the father of modern management” first conceived this approach during his study of General Motors in the 1940s. His first book Concept of the Corporation published in 1946-detailed “management by objectives” (MBO) (Davison & Keil, 1999).

Even though Drucker first wrote about MBO in 1946 it didn’t gain popularity in business until the 1970s (Doherty, 1994). MBO is an important tool of management as Goal Analysis is an important tool of Education. MBO allows the project manager to communicate goals set in the definition phase to be realized during the Implementation phase. As Doherty puts it “The intent of Management by Objectives (MBO) is to integrate work efforts of an organization by cascading goal setting downward so that as goals are achieved at the lowest levels they support achievement at higher levels.”

Drucker was not alone in the development of this management approach. George Odiorne, a professor at the University of Massachusetts, was also important in the development of the Management by Objectives (MBO) approach (Tyack, 1995). Odiorne defines MBO as “a system in which the first step of management is the clarification of corporate objectives and breaking down of all subordinate activity into logical subdivisions that contribute to the major objectives (Tyack, 1995).” This breaking down of “all subordinate activity” leads us to the next step in the KT model the “Work Breakdown Structure.”

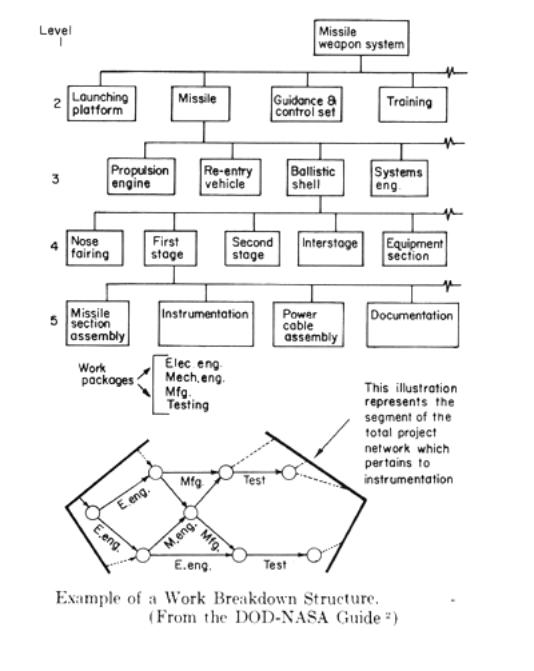

Work Breakdown Structure

This third step in the KT model the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS), is “to identify the results necessary for meeting the project objectives (Kepner-Tregoe, 1993). It “identifies and displays the deliverables and accomplishments for the project (Kepner-Tregoe, 1993).” A project manager in this step redefines the objectives in terms of deliverables or accomplishment. These deliverables are then further broken down into the Terminal Elements (the lowest level of deliverable or accomplishment). The end result of this step is the total cost of all the Terminal Elements. Frame describes the WBS as a “bottom-up” approach to cost estimating (Frame, 1994). This may sound a bit backwards, but what Frame means is that before cost estimates can be made a WBS must be developed and then from the bottom most elements the cost estimate is determined.

Believe it or not… the WBS, the third step in the KT model, was not developed until after the sixth and seventh steps (Sequence and Schedule Deliverables). This development process is better described in latter sections of this paper (see Critical Path Scheduling). The WBS was originally developed as a part of the NASA-PERT model in 1963 (Moder & Phillips, 1964). The KT WBS comes in to us in two varieties: a Diagrammatic (flow chart-like) version, and a text-based (list-like) version (Kepner-Tregoe, 1993). NASA developed the diagrammatic version that KT recommends. An example of a NASA-PERT WBS is available in Appendix B.

The KT model, in addition to describing a diagrammatic or flowchart version of the WBS, also recommends a text version. The next phase in the development of the KT model, the text-based WBS was an important one. This makes possible the next few steps Resource Requirements and Responsibility Assignment Matrix. Basically these steps are a continuation of the WBS in a series of text-based charts.

Identify Resource Requirements

This step in the KT model allows a project manager to determine “the inputs (resources) necessary to provide the project deliverables and accomplishments (Kepner-Tregoe, 1993).” In other words this step lists all the “things” necessary for the completion of the project. These might be Human Resources such as knowledge and skills, or person hours required to accomplish as task. Or they might also be facilities, equipment, materials or supplies.

The Project manager fills the matrix created by the WBS on the Y-axis and the Resources listed on the X – Axis.

Planning Phase

This phase is composed of four more steps. They are Assign Responsibility, Sequence Deliverables, Schedule Deliverables, Schedule Resources, and Protect the Plan. At this point in the project, a foundation has now been laid by the Definition phase. Also, now is when the Project manager makes or breaks the project. The manager needs to plan ahead and set up for the 3rd and final phase the Implementation phase.

Project Management Discussions

Throughout the three phases of the KT model, the project manager is expected to conduct Project Management Discussions. It is during the Planning phase that these discussions become crucial to the overall plan. These discussions act as a feedback mechanism to the Project manager and allow him/her to track and monitor the progress to the project. If the project is heading in the wrong direction, feedback that these discussions provide can alert the project manager to important issues that he/she may have to challenge.

At any point during the project, the project manager may conduct formal or informal formative evaluations of the project (Tessmer, 1993). To use Tessmer’s words a formative evaluation is “the systematic tryout of instruction” [or business] “for the purposes of revising it (Tessmer, 1993).” Tessmer was writing from an educational perspective, but his principles of formative evaluation translate perfectly to business. A formative evaluation unlike a summative evaluation is conducted throughout the development of a project or product. This may be as simple as a one-on-one discussion with a key employee, an expensive field test of the product, or an in depth study of just one component of the final project. Again this of course, depends upon the complexity and importance of the project (Tessmer, 1993).

Assign Responsibility

Assign Responsibility, the fifth step of the KT model involves the completion of a Responsibility Assignment Matrix (RAM). This RAM is a continuation of the third step the WBS. This matrix has the WBS on the Y-axis and people or departments along the X-axis. The work to be done to complete the terminal elements in the WBS is then briefly described in the matrix cells.

Critical Path

Scheduling

The Work Breakdown Structure, though separated from Sequence Deliverables and Schedule Deliverables, by the KT model, was originally developed in the late 1950’s as a part of a system of planning techniques with Sequence and Schedule Deliverables. As Horowitz puts it this “is one of a family of planning techniques, which includes PERT, among many others.” This family of techniques he calls Critical Path Scheduling. Kepner & Tregoe were involved in the development of these techniques to some degree, as the RAND Corporation employed them during this period. However, it was two groups working in parallel that finally developed this management control system (Horowitz, 1967).

In 1957, a team of engineers and mathematicians, employed by Du Pont and the Sperry Rand Corporation, developed and successfully employed a system capable of scheduling complicated design, construction, and plant maintenance projects. This management control system came to known as the Critical Path Method (CPM) (Horowitz, 1967).

In a parallel project, the U.S. Navy working in conjunction with Booz-Allen and Hamilton, a management firm, completed the development of a management control system. This system was design to manage and control the Fleet Ballistic Missile Program. This technique called PERT (Program Evaluation and Review Technique), was used to produce the Polaris missile system in 1958 (Horowitz, 1967). The focus of the original PERT was as a scheduling tool; it also made use of statistics to determine the likely hood of a project success.

There were quite a few differences between the original versions of the CPM and PERT techniques. A key difference between the original CPM and PERT is where the activity lies in the diagram. Originally, the CPM networks developed by Du Pont & Sperry Rand were “activity on the arrow” network diagrams (Horowitz, 1967). The PERT network diagrams, developed by the Navy/Booz-Allen and Hamilton group, were “activity on the node” diagrams (Horowitz, 1967). But in the intervening years the PERT and CPM methods have merged and changed quite a bit (Moder & Phillips, 1964).

In 1962, the Air Force developed their own version of PERT called PERT/Cost, when they added resources estimates to the logic networks. The initial version of PERT was thereafter known as PERT/time (Fleming & Koppelman, 1998). The system developed by NASA in 1963, (which was used to a man on the moon!), NASA-PERT, did away with probable completion statistics and now makes use of the single activity time estimate which is characteristic of CPM (Moder & Phillips, 1964).

Sequence Deliverables

This step in the KT model involves the development of a CPM Network diagram. As you might expect the KT model specifies that their Critical Path diagrams should be drawn or developed as “activity on the node” diagrams much as NASA-PERT did in the 1960s.

Today project managers use a number of software packages to aid in the development of these network diagrams. Probably the most popular of these packages is Microsoft Projectă. A mistake that many novice project managers make, is to begin a project by sitting down to the computer first. Project managers should go through the preceding steps in the KT model before building a network diagram (M. Karim, personal communication, February 3, 2000). It is up to the project manager to define the goals, plan tasks and resources, and implement and manage the project, but software can greatly simplify the task of calculating the schedule (Lowery, 1990).

Obviously it is not a requirement of the KT model to use project management software in the production of these diagrams. Kepner and Tregoe teach novice managers that there is a five-step process to produce a network diagram “from scratch.” Here are those five steps:

1. Determine if the activity-on-node or activity-on-arrow format will be used.

2. On the left side of the page a start node is developed and on the right side a finish node is developed.

3. Using the precedent relationships that have been developed earlier, a network of the terminal elements is drawn beginning with the start node and ending with the finish node.

4. Review the network to make sure that every node, with the exception of the start and finish nodes, has at least one entering and one exiting arrow.

Finally the project manager finds the Critical path. This is “the path through the project network that determines the shortest time within which the project can be completed (Kepner and Tregoe, 1993).” The project manager can then use this critical path to proceed to the next step in the KT model – Schedule Deliverables.

“Scientific Management”

The next step in the KT model – Schedule Deliverables - is the production of a Gantt chart. This tool is perhaps the oldest technique of the KT model. This chart comes to us from the work of several pioneers of the Industrial Revolution. At the end of the nineteenth century Frederick W. Taylor, Frank G. Gilbreth, Henry L. Gantt and several other pioneers began to question how production in the factory was being conducted (Juran, 2000). Their ideas soon became called “Scientific Management.”

Scientific Management began with the ideas of one young foreman working in a steel company. Frederick Winslow Taylor at age 24, (1880), became foreman at the Midvale Steel Company in Pennsylvania. It was here that Taylor first derived the ideas that later led him to write his 1911 classic “The Principles of Scientific Management (Kanigel, 1997)”

Much of twentieth century life has its origins in Taylor’s work. Taylor was simply interested in producing an efficient system. As a foreman, at the Midvale Steel Company, Taylor began by studying the time it took each worker to complete a step, and watch how that changed when he rearranged equipment. These time-motion studies, as they were called, have made a big difference in what we do today. By studying workers in action, Taylor soon learned that he could dramatically increase efficiency in the workplace (Kanigel, 1997). These simple ideas eventually developed into what would be called the “Scientific Management movement.” It is the vision of this movement to which we owe much of the prosperity of the twentieth century (Kanigel, 1997). The KT Project management model is the logical evolution of the dreams and ideas begun a hundred years ago.

Schedule Deliverables

As mentioned earlier, this next step in the KT model – Schedule Deliverables is the production of a Gantt chart. Gantt, a follower of Taylor, developed this technique around 1900 (House, 1988). In terms of the KT model, quite simply it is a Calendar-style bar chart attached to the WBS. This device is useful in the early stages of the project for putting perspective on the project (Kliem, 1986).

The Gantt chart however, has several limitations. It does not reflect the relationships between different deliverables. It also does not describe the dependencies of the phases or events (KT calls these “precedences”). The also do not show the effect of delay .Nor does the Gantt chart show percentage of total work. Lastly if a revision to the project is made a new chart must be produced to represent the change. It is little wonder that the CPM and PERT methods were developed (Kliem, 1986).

Protect the Plan

Here is the heart of Project Management; and where Kepner and Tregoe shine. In the late 1950s, and after they left the RAND corporation, Kepner and Tregoe developed two techniques that earned them a great deal of admiration from the business community. These two techniques came to be called Potential Problem Analysis and Potential Opportunity Analysis (Kepner and Tregoe, 1993).

Potential Problem Analysis (PPA)

A Potential Problem Analysis matrix is similar to the WBS device described earlier. It is a preventative measure that makes use of a matrix information system. This matrix is used to organize and create solutions to potential problems that a project manager might have.

This matrix lists along the Y-axis the WBS terminal elements in question. But in addition to that element, it describes some potential problem that might not evolve if that terminal element were to have something go wrong. It is not necessary to perform a potential problem analysis on all WBS terminal elements, but again “prevention is the best medicine.” Along the X-axis are listed - Likely causes, Preventive Action, Contingent Action, & Trigger. A Trigger is an event that activates the contingent action. In this step the project team develops preventative actions –actions that stop the onset of difficulties; and contingency actions – that minimize damage from a potential problem.

Potential Opportunity Analysis

This technique is nearly identical to the Potential Problem Analysis with the exception of one major component. Rather than include potential problems, the project manager includes potential opportunities.

As an example: The project is the building of a house. If the lumber for the house arrives three day early and there is now reason to halt construction the project manager (a sub contractor in this case) could call in the carpenters to begin construction. This is a potential opportunity that like a potential problem can be foreseen and entered in the PPO matrix.

Implementation Phase

This last phase may seem all too easy for the Project manager and they may perceive a model as unnecessary. But Kepner and Tregoe have broken this phase into four steps. Each of these steps provides helpful pointers from years of studying Project Managers in action.

Start to Implement

When to start may seem like a simple question, but a false start could lead to problems. The Project manager should inform the team of when to start. This way WBS elements will begin at the right time and not halt the process if late or cause unforeseen cost if they start early. This will also maximize the commitment from the project team as well as insure focused involvement (Kepner and Tregoe, 1993).

In large projects it is even suggested that there be a formal “kickoff” meeting. This may include the entire project team, all of the resource managers, and any stakeholders (Kepner and Tregoe, 1993).

Monitor Project

A well-designed project is prepared for any contingency. This is when the PPA becomes all to important. In addition to the PPA, Kepner and Tregoe teach novice Project Managers that there are two key principles to keep in mind when monitoring a project:

A clear standard of performance – In understanding performance the project manager might take a number of approaches. One of the most obvious approaches is to gage level of completion. This must be done with clear measurable objectives in mind. The answer “Oh we’re about 50% done” is not sufficient

Accurate feedback on project performance – As mentioned earlier, the project manager may conduct formal or informal formative evaluations of the project (Tessmer, 1993). These may be as simple as a “one-on-one” meeting with a resource manager or they may be more in-depth on larger scale projects.

A key concept that that is included in the KT model is the use of “milestone” to denote progress. Milestones are “the road sign that the manager checks carefully before preceding (Kepner and Tregoe, 1993). Milestones, in other words, are important events or accomplishments that signify a level of completion.

“Monitoring the Project” is what most project managers think of when they think of an implementation phase. However there are other considerations in this phase.

Modify Project

Modifying a Project does not have to be disaster. Even though some projects are carefully orchestrated, a change in plans the end of the world. Depending upon the complexity of the change and the complexity of project the Project manager has two things to keep in mind. Number one is a calm project manager makes better decisions and number two is communication with team members is very important in a time of crisis. However this communication should be carefully orchestrated as well else panic can set in and cause even more problems.

Closeout and Evaluate

This the final step in project management is often forgotten. Just as it is important to start a project on time it is also important stop a project on time. Else unforeseen costs and cost overruns are possible.

First of all it is important o begin an evaluation process, before calling a halt to the project. It is important for a project manager to determine if all the objectives of the project have been accomplished. If necessary, consult upper management to determine if all objectives are complete.

This type of evaluation process is called a summative evaluation. These to can range from very complex processes to very simple techniques depending upon the complexity of the project.

Discussion

The Kepner Tregoe Project Management Model has been developed as a number of interconnected techniques and practices over several decades. Earlier in this paper, the telephone was given as an example of the concept of invention by synthesis. Perhaps a better example is the Modern Automobile. Just one individual did not invent this either. Many different groups developed the Modern Automobile over many decades. The Car radio was not even dreamed of, a hundred years ago when the first cars rolled off the assembly line. Punctureless tires, air conditioning, hydraulic suspension, and transmission coolant systems… the list goes on and on.

The point here is not that Kepner and Tregoe had nothing to do with the KT model! Quite the contrary, Kepner and Tregoe were very much involved with its design and development. The point is that many individuals and groups were developing the various components of the Kepner -Tregoe model in parallel over a comparatively long period of time. This model has a rich history reaching back before Kepner and Tregoe were even born. Most processes and techniques are far older and far more complex than most people realize.

History shows us, that “true invention” is a very rare event.

References

Burke, J. (1978) Connections Boston, Mass : Little, Brown and Company

Davison, A., Keil , A. Peter Drucker, (1999) The father of Modern Management to make rare keynote appearance at Xplor ’99, available online: http://www.internetwire.com/technews/tn/tn982249.htx

Doherty, L.

(1994) Performance Agreements--MBO Revisited? : Presented at the Seventh

Annual National Conference on Federal Quality, Available online:

http://tql-navy.org/speeches/mbo.txt

DOD and NASA Guide, PERT Cost System Design, Department of Defense and National Space Administration, Government Printing Office, Washington 25, D.C., June 1962

Fleming, Q.,

Koppelman, J. (1998) Earned Value Project management: A powerful Tool for

Software Projects, Available online:

http://stsc.hill.af.mil/crosstalk/1998/jul/value.asp

Frame, J. (1994) The new project management: tools for an age of rapid change, corporate reengineering, and other business realities San Francisco, Ca.: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Kliem, Ralph (1986) The Secrets of Successful Project Management New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Kanigel, R. (1997) The One Best Way: Fredrick Winslow Taylor and the Enigma of Efficiency New York: Viking

Horowitz, J. (1967) Critical Path Scheduling Management Control Through CPM and PERT New York, N.Y.: The Ronald Press Company

House, R. (1988) The Human Side of Project Management. Beverly, Mass: Addison-Wesley.

Juran J. (2000) Pioneering in Quality Control , Available online:

http://www.juran.com/research/articles/SP626.html

Kepner, C., Tregoe, B. (1965) The Rational Manager New York, N.Y.: McGraw Hill Book Company

Kepner, C., Tregoe, B. (1981) The New Rational Manager Princeton, N.J.: The Princeton Research Press

Kepner, C., Tregoe, B. (1993) Project Management Notes and Reference Kepner-Tregoe Inc.

Lowery, G (1990) Managing Projects with Microsoft Project for Windows New York Van Nostrand Reinhold

Mager, Robert. (1982) Preparing Instructional Objectives. 2ndEd Palo Alto: California: Fearon Publishers.

Moder, J., Phillips, C. (1964) Project management with CPM and PERT New York, N.Y.: Reinhold Publishing Corporation

Tyack, D. (1995) “Reinventing Schooling” in Learning from the Past Eds. Ravitch Vinovskis Baltimore, MY : The John Hopkins University Press

Tessmer, M (1993) Planning and Conduction Formative Evaluations: Improving the Quality of Education and Training London: Kogan Page

Tyler, R.W. (1949) Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction. Chicago: University of Chicago

Smith , E.R., and Tyler, R.W. (1942) Appraising and recording student progress. New York: Harper and Row

Wilburg, Karin M. (No date) An Historical Perspective on Instructional Design: It is Time to Exchange Skinner's Teaching Machine for Dewey's Toolbox? [Online]. Available: http://www-cscl95.indiana.edu/cscl95/wiburg.html [1998, September 19]

Worthen, Blaine R. and Sanders, James R. (1987) Educational Evaluation : Alternative Approaches and Practical Guidelines. White Plains, N.Y. Pitman Publishing Inc.

Appendix A : The Kepner Tregoe Project Management Model

Appendix B :

NASA-PERT Work Breakdown Structure

Source: Moder, J., Phillips, C. (1964) Project management with CPM and PERT

Appendix C: Text-based Work Breakdown Structure

Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) Project Statement: Move the Corporate

Customer Services department within two months (at a cost not to exceed $59,500). Work Breakdown Structure: 1. Office Layouts Drawn 1.1 Relationships charts prepared 1.1.1 Interviews conducted 1.1.2 Charts prepared 1.2 Department block layouts drawn 1.3 Department detailed layouts drawn 2. Office Equipment Obtained 2.1 Equipment to keep identified 2.2 Equipment to order identified 2.5 Office interior designed 2.4 Equipment and office furnishings

ordered 2.5 Equipment and office furnishings

received 5. Office Ares Prepared 5.1 Electrical services installed 5.2 Telephone services installed 5.5 Computer services installed 4. Office Moved 4.1 Work order submitted 4.2 Equipment moved per schedule 4.5 Equipment installed per schedule 4.4 Personal materials moved per schedule 5. Organization Manuals Updated 5.1 Customer notices distributed 5.2 Personnel database updated 5.5 Telephone directory revised

Source: (Kepner-Tregoe, 1993)

Appendix D: Project

Management Timeline

1881-

Frederic Winslow Taylor introduced the notion of “scientific 1942 – Smith and Tyler publish their report on

The Eight Year Study 1949- Tyler publishes. Basic Principles of

Curriculum and Instruction, Objectives – based Education 1957 - Du Pont/Sperry Rand - Critical Path Method

(CPM) - developed and successfully employed a system capable of scheduling

complicated design, construction, and plant maintenance projects. 1958 - U.S.

Navy/Booz-Allen and Hamilton - PERT (Program Evaluation and Review

Technique), used to produce the Polaris missile system 1963

– NASA-PERT is developed 1965 – Kepner

& Tregoe Publish The Rational Manager 1969 – Man Goes

to the Moon 1981 – Kepner

& Tregoe Publish The New Rational Manager 1993 –

Kepner-Tregoe Assoc. Publish Project Management

![]()

management”